BY LEA KREININ IN BOOKS, CULTURE · MAY 8, 2019

Lea Kreinin interviews the Scottish publisher, Allan Cameron, who has started to publish Estonian literature in English.

Allan Cameron is a Scottish writer, translator and publisher who lives in Glasgow. He has already published translations of several books from Estonian literature, by Anton Hansen Tammsaare, Andrei Ivanov, Mari Saat and Rein Raud. Tammsaare’s “Truth and Justice vol I” will be available soon. Cameron was discussing life and literature with Lea Kreinin. The full interview with Cameron will be featured in the Estonian Literary Magazine, published in autumn 2019.

Nowadays, so many books are issued every year and some people may think, why bother to publish even more. What has led you to open your own publishing house?

There can never be too many books! Just as there can’t be too many conversations, because language is what people do. The merchant class of the Middle Ages and modern capitalism have always had a utilitarian approach to language, which is often philistine, but also occasionally capable of its own aesthetic. Machiavelli’s prose style is more akin to the modern English than to literary Italian of any age. It is pared down; it is minimalist.

The more people get involved in literature, the better. We’re not in competition with each other, but rather feeding off each other in an endless debate among ourselves and with the dead. I would like to see the return of the long sentence to English literature, but I’m probably alone in that.

Like many things in my life, I got into publishing by chance. I had already translated well over twenty books from Italian, and I had had two novels of my own published in Edinburgh. I then wrote a non-fiction work on language, and it had attracted the attention of some leading literary figures, so I was slightly upset when my publisher wanted to make changes to it (he may have been right).

I decided to strike out on my own and publish it myself. Strangely, it was quite successful and received further plaudits. I then incorrectly assumed that publishing is an easy business. I went into translated novels and initially lost a lot of money, which I have since been trying to pay off. It is difficult to assess whether this was the right thing to do. The upside of publishing is that it’s a collaborative exercise, unlike writing and translating which are solitary occupations.

In the recent years, you have also issued many Estonian books. How did you “find” Estonian literature, what led you to it?

The fate of small nations has always been important to me, partly because of my experience of Bangladesh, which was called East Pakistan when I lived there. Terrible things happened that went unreported because the United States, China and Pakistan formed one regional alliance and India and the Soviet Union the other. The actual reality on the ground was of no interest to anyone in power. Of course, there were more Bengalis than Pakistanis, but they couldn’t join the army and the status of their language was not secure.

Self-determination is a fundamental right and doesn’t only affect small nations, but attitudes to it are often selective, today just as they were then. I have also been fascinated by lesser-spoken languages. This is, in part, because my mother was a Gaelic-speaker, and I spent some summer holidays on a croft in the Scottish Highlands where Gaelic was spoken. My wife is a Gaelic-speaker and my son goes to a Gaelic school. My mother’s attitude to her native tongue was strangely conflicted. She was both proud and ashamed of it. She identified it with the peasantry and felt that she had risen above it.

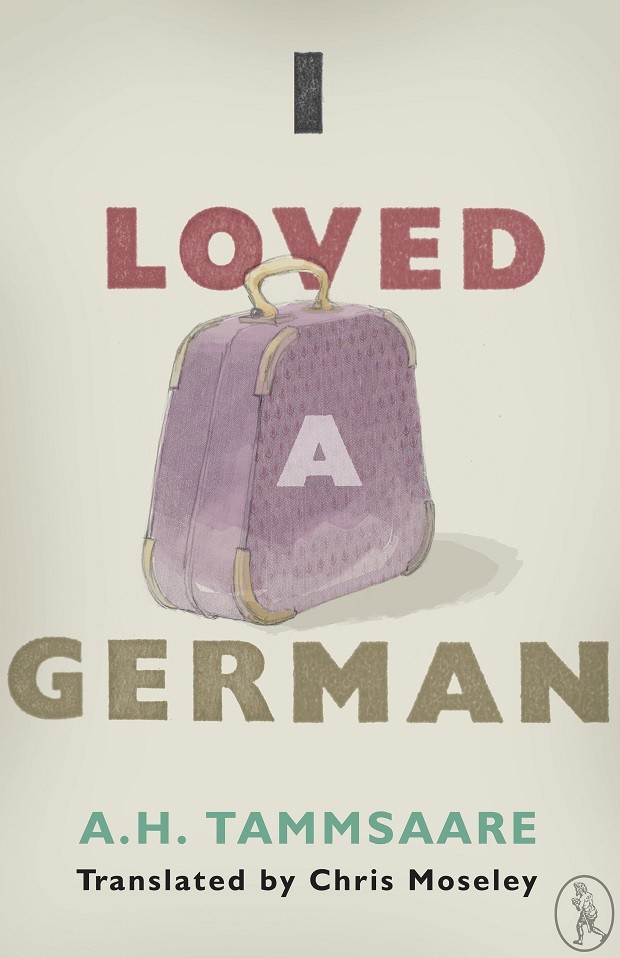

So, I can easily understand the conflicted attitudes of Oskar in Tammsaare’s “I Loved a German”, because people who have been excluded over many centuries, rebel mentally against their status – but also accept it in their actions and habits, because they have to. Once the dominant power is removed, either through conflict or through a collapse of that power (or powers in the case of Estonia, caught as it was between the Teutonic Knights, Sweden and Russia), the psychological damage and uncertainty endures for some time.

On my first visit to the London Book Fair, I gravitated to the Estonian stand and had a long conversation with a woman who had been called in at the last minute, because the volcano that exploded in Iceland had prevented most people from attending. I took a copy of the pamphlet with several suggestions for translation, which included Mari Saat’s “The Saviour of Lasnamäe” – our first Estonian book.

You have visited Estonia. What is your impression and opinion of our country?

I first visited Estonia in 2014 and had a wonderful time. It was very interesting to meet Estonian writers and hear about their work. Like most small countries, Estonians are great linguists, and this is something I greatly admire.

Citizens of large countries often think of small countries as provincial, but the opposite is true. Provincialism is essentially the tendency to believe that all knowledge and good practice is contained within the entity the provincial person identifies with, but no small nation can believe this. Small nations are outward-looking, and large nations are inward-looking. The English-speaking world or the Anglosphere is an extreme example of this “provincialism of the powerful”. This is why I am so committed to translated literature. English badly needs translation.

Eastern Europe generally retains some of the virtues destroyed by neoliberal economics elsewhere – a greater sense of community and a proper understanding of fundamental human values. To put it another way, they resemble the societies of my childhood in some ways (it is of course more complicated than that).

It is also true that Eastern Europe is understandably quite right-wing in its attitudes, given recent history, but the problem is that when one series of problems is removed, another completely different one takes its place, and these could be just as toxic. Machiavelli argued that the truths that are useful to us in one period are not in another, so we have to adapt constantly to a changing world. This must be truer now than in his day. Having said that, I think Estonia is dealing better with the new reality than some other countries that have emerged into the post-Soviet world.

Do you think Estonia and Scotland have something in common? What would it be?

Undoubtedly. We were more similar in the nineteenth century. The land belonged to large estates often run by people who spoke a different language. The status of smallholders and landless peasants was very similar (this is clear from the first volume of “Truth and Justice”), as were the economic autarky of peasantry and influence of the pastor or minister in those small societies.

In fact, Scotland resembled Estonia more closely than it did England in this sense. The reason was in part climatic: large tracts of marshland, long winters without little light and relatively low populations favour a certain kind of landownership (although, distance from large markets could be the decisive reason, as similar landownership existed in southern Italy and southern Spain). In Scotland, much of the abandonment of the land took place in the nineteenth century and the population has since been concentrated in the more fertile “Central Belt”, which became highly industrialised (but is no longer). Our language has almost disappeared, and our culture has been weakened.

The reason why Estonia is doing so much better is that it gained independence in 1918 and was able to develop sufficient self-confidence to survive the Soviet period. Scottish nationalism today is not about “land and blood”, because Scotland is a social-democratic country that would like to distribute wealth and public services more equitably, something that we’ll never achieve as part of the UK.

The Scottish National Party is the only government party in Europe that actively supports immigration, acknowledging that immigration, far from being a problem, is actually a way to revitalise a society. This is perhaps the most important thing we have achieved: a new definition for small-country nationalism in the twenty-first century.