Invented in Troyes, these travel-sized texts started popping up everywhere.

NO MATTER WHERE YOU ARE in the world, during any given morning commute, you will likely see a book. Whether that book is electronic and read from a screen, or a more traditional three-dimensional version in the grasp of a hand, the fact remains: people like to read on the road. In 2018, it’s easy enough to compress a text into a never-ending scroll of a PDF and attach it to an email, which is equally digital and shockingly fast. But in the 17th century, sharing a piece of literature was exclusively tactile and decidedly more slow-going.

Troyes is a town in northeast France that sits on the Seine in the Champagne region. It is known for being a main stop on the ancient Roman travel route Via Agrippa, and the site where the standard measurement for gold evolved. It is also responsible for the mass production of literature in France.

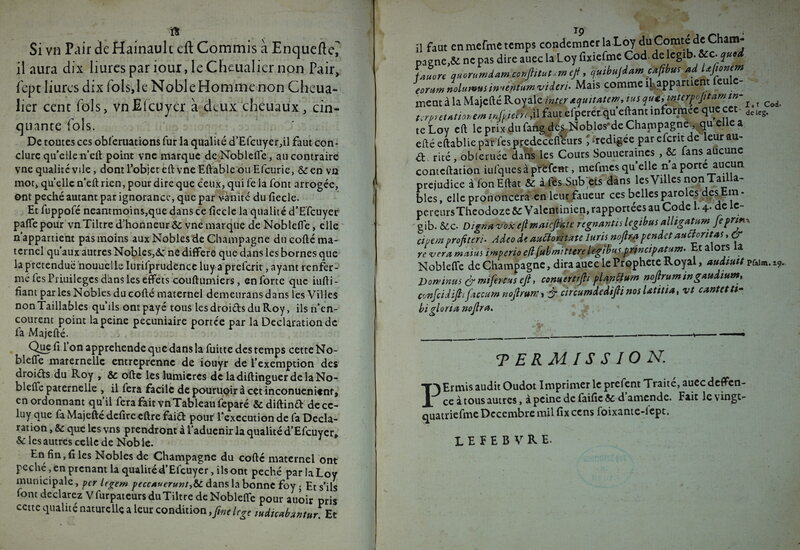

In 1602, brothers Jean and Nicolas Oudot were printers in Troyes, and sustainably minded to boot. Using recycled paper from previously published books, the innovative printmakers created low quality, travel-sized brochures, protected with covers made from used sugarloaf packaging the color of faded denim. These updated editions of classic texts (think fun-sized SparkNotes) this small-format printing model birthed were thus named livres bleus (blue books). Blue books, and the broader Bibliothèque bleue (blue library) publishing house, were made possible through the Oudot brothers’ association with the family of Claude Garnier, who was a Renaissance-era printer of popular literature himself, primarily for the king of France.

Admittedly, these blue books were not beacons of perfection. They were littered with typos and misaligned margins, and had a reputation for being highly (read: egregiously) abridged versions of their parent text, but the possibilities they contained were remarkable nonetheless. The brothers Oudot diluted their literature for a much wider (and less literate) audience, and it wasn’t long before the simplified volumes became relatively mainstream. Because they were cheap to make they were cheap to buy, thus increasing the lower class’ access to books. In a 1979 study, American historian Elizabeth Eisenstein argued that printing was “the unacknowledged revolution” of the Renaissance, due in part to the blue library’s role in situating printed matter as a significant part of popular culture.

The tiny texts, measuring 12 by 7 centimeters (4.7 by 2.8 inches), were also easy to carry on one’s person, which gave birth to our term “pocket book.” Their miniature size made for easy transport, so blue books, small and light, became a perfect vehicle for the popularization of mass media. Book-peddling colporteurs created a network of wide distribution across France by selling the petite books at various fairs and markets. Printers used colportage, this system of literary circulation, to spread their cheap, abridged editions of popular texts to rural areas of Europe in particular, as book shops were exclusively found in major cities. In this way, blue books increased literacy in working-class populations dramatically. Though the Oudot brothers initially focused on reprinting and repurposing local literature, their blue book format took hold in other French cities and towns—proving that readers beyond Troyes, including those in urban environments with the capital to purchase classic works, were devoted to the new blue library. (Even noblewomen read them!)

As the years—and the success of blue books—marched on, the blue library became a bonafide family affair. Jean and Nicolas’ sons, four between the two of them, ran the production of blue books in the late 17th century. The family’s eventual literary imprint in Paris, cemented by its publication of satire, religious literature, cook books, and almanacs in large quantities, nearly secured them a printing monopoly over popular French works. But in 1760, the Oudots finally went out of business, as new legislation infringed upon the right to reprint literature.